|

A few weeks ago, I was part of a small group of faculty and donors who presented a workshop for student finalists in the annual pitch competition hosted by the entrepreneurship center in the college of business. Since the finalists are from a variety of disciplines, and have different experiences in business and public speaking, the workshop was designed to offer guidance on what they should include in their slide decks, tips on public speaking, stage presence, and so on.

0 Comments

In part two of our interview with textile artist Janice Lessman-Moss (episode #211), we noted the substantial volume of artwork she created over her lengthy career. That prompted Andy to ask how she keeps track of her work—does she catalogue it, photograph it, and so on. She responded with her approach to documenting her artwork, and how it has changed over the years to keep pace with technology. Here’s a summary of the data Janice keeps on each piece of art:

When speaking with friends recently, we recalled a few comments we received from arts teachers over the years that centered on assumptions and misperceptions about arts entrepreneurship courses. They included:

There’s a lot to unpack in these comments, and because it’s likely those who teach arts entrepreneurship might participate in similar conversations, I thought it’d be worthwhile to address each of them: Last month, Andy and I interviewed Colin Currie for a podcast episode that will air in early 2023. He’s the most dynamic and sought-after percussion soloist and performer working today. Beyond playing concerti with orchestras and solo recitals around the world, he’s busy working in other ventures he created: a mixed chamber ensemble, a percussion quartet, and a record label. I know people who have careers in each of these fields, but for one person to build a portfolio career that encompasses all four, and from scratch, is rare. In my opinion, Colin is a serial entrepreneur in the genre of music.

Interestingly though, when I asked if he sees himself as an entrepreneur he said “no.” At first, his response took me by surprise, because I wondered how someone who earns a living and employs people in several arts organizations he created, couldn’t see himself as an entrepreneur. But as the dialogue continued, it became apparent that the artist management companies with which he works look after most of his back-end activities, from arranging performances, accounts receivable, travel, and so on. That would assuredly free up his time to allow him to focus mainly on the activities integral to being a musical artist: practicing, rehearsing, performing and recording. So from that vantage point, I can appreciate how he might not see himself as an entrepreneur. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that my posts are sometimes inspired by classroom discussions. This month’s post was prompted by a statement my wife Diane made last week when she was speaking in my Music Career Development and Entrepreneurship class about career development and future employment as an administrator at an academic institution.

She was telling the class that when she was a piano professor, she would encourage her students to “reverse engineer” their paths to achieve their professional goals. Essentially, they should start with the end in mind for a better understanding of what a successful path to attain a college teaching position might look like. One exercise Diane said was particularly effective was to have her students review past and present job postings to note the requirements for each, and cite any patterns and anomalies: e.g., Which experiences were preferred? Which hard and soft skills were they looking for? In recognizing this, the students could better chart a path that would help them take the requisite courses, pursue various teaching and performing activities, take on leadership roles, and so on. In a recent Music Career Development and Entrepreneurship class, we were speaking about how the arts are commonly seen as a want rather than a need, and that the arts are competing not only with each other for the same discretionary funds, but also with sporting events, recreational events, and hobbies. I told the following story about a short-lived music retailer to emphasize the point: Back in the 1990’s, the founder of a highly successful office supply superstore decided to launch a musical instrument company using the same model that brought him success in office supplies. There were a variety of reasons why the model didn’t work in the music products industry, but I half-jokingly said, “Most of the population will at some point today need a pen or a piece of paper, but they likely won’t need a trombone.”

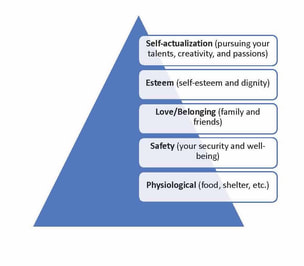

Later that day I happened to read an article about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs--and it hit me that the arts fit very clearly at the top of the hierarchy. A quick online search yielded many articles confirming that sentiment. Above is a summary (with my interpretations) for those who don’t remember or haven’t heard of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. This series of blog posts is centered upon the idea that to truly know an art, one should investigate every aspect of it. This mindset helps arts entrepreneurs sharpen their thinking by considering all the activities in the arts value chain, beyond the act of creating art, that are needed to deliver their offerings. This will result in making better-informed business decisions, as well as limit risk because only the most effective and efficient reasons for why, how, when and where to deploy resources make it through the evaluation process.

In Part 1, I highlighted how changing a few of the attributes of implements used to create art can impact their utility and value. In this post, I’ll identify select elements to consider when marketing art or arts related items, and how it can impact your brand and interest in your offerings. Keep in mind these elements are presented in a vacuum because budgets, timelines, customer segments, etc., aren’t considered in this post. In the seven or so years I’ve been teaching arts entrepreneurship courses, I’ve also been researching and speaking with colleagues, students, and entrepreneurs about the topic, with the goal of blending experience and theory to create modules that better prepare students for their futures. Based on my anecdotal findings, it appears much of the focus in the discipline is on helping artists (in any arts medium) understand how they can make a living delivering their art to the world. Certainly there are variances, but that’s the common theme. While it’s a solid approach, it doesn’t account for, nor contextualize, the variety of opportunities available to students throughout the arts ecosystem.

For centuries, art of all kind has been controlled to varying degrees by “gatekeepers”—those who have the power to determine which art is created or accessible, or both. There are plenty of examples: from artists who have benefitted from the largess of royalty or the Church; to gallery owners and powerbrokers in the visual arts; to publishing houses; to movie studios, and even in the recent past when some governments around the world only permitted art they approved.

As technology has developed, so too have the mediums for the exchange of ideas, and those ideas are spreading faster and farther than ever before. The result is that the gatekeepers are being marginalized, repositioned, and in some cases replaced. An example in the arts is desktop publishing, which has allowed musicians, poets, and other artists to self-publish and reap more margins. It also lessened the dependency on established publishers. Those publishers have felt the pinch in the past few years through the loss of business from self-publishing, and the ease for new and nimble publishing houses to be formed. The prevalence of home studio software caused a similar arc in the recording industry over the past 10-15 years. It’s easy for bands to produce their own music, and it’s common for musicians to record tracks in their home studios and send them to producers instead of traveling to record in a studio. We’ve also interviewed visual artists on our podcast who have vibrant websites, through which they sell much of their art. Arts Entrepreneurship classes have grown in popularity over the years, and for the past 5-10 years, universities, conservatories, and art schools have been adding them on a regular basis. It’s the same for minors, certificates, and majors. That’s a good thing because institutions should provide students with tools and methods they can use to apply their art, and make them aware of the variety of opportunities throughout the arts economy.

That said, if you speak with college students, their parents, or even those who teach the subject, a question that often comes up is, “What’s arts entrepreneurship and how does it vary from regular entrepreneurship? It’s a good question, and the answer depends on the entrepreneurial experiences of the person you ask. |

AuthorsLearn more about the authors. Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed